Some forms of food processing, such as pasteurization, have public health benefits. However, processed foods and beverages have the potential to negatively impact health when their regular consumption is likely to contribute to excess sodium, free sugars, or saturated fat. This section focuses on these foods and beverages and how their regular intake over time can contribute to poor diet quality. Prepared foods and beverages from restaurants and other similar establishments, and those prepared at home can also contribute to excess sodium, free sugars, or saturated fat. Though less healthy choices will be made at times, what matters most is what people consume on a regular basis. Table 3 lists convincing findings that support Guideline 2.

GUIDELINE 2

Processed or prepared foods and beverages that contribute to excess sodium, free sugars, or saturated fat undermine healthy eating and should not be consumed regularly.

CONSIDERATIONS

Sugary drinks, confectioneries and sugar substitutes

- Sugary drinks and confectioneries should not be consumed regularly.

- Sugar substitutes do not need to be consumed to reduce the intake of free sugars.

Publically funded institutions

- Foods and beverages offered in publically funded institutions should align with Canada’s Dietary Guidelines.

Alcohol

- There are health risks associated with alcohol consumption.

Processed or prepared foods and beverages that contribute to excess sodium, free sugars, or saturated fat undermine healthy eating and should not be consumed regularly.

Rationale

Many terms such as ‘minimally processed’ or ‘ultra-processed’ are used to categorize foods as healthy or unhealthy. The term ‘highly processed products’ is used in this report to describe processed or prepared foods and beverages that contribute to excess sodium, free sugars, or saturated fat when consumed on a regular basis. This includes processed meat, deep-fried foods, sugary breakfast cereals, biscuits and cake, confectioneries, sugary drinks, and many ready-to-heat packaged dishes.

In recent years, the availability and consumption of highly processed products has increased significantly. 1 This shift in consumption patterns has been linked to the global rise in obesity rates. 2 3 Obesity is a risk factor for many chronic diseases including cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and some types of cancer. 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Taking action to reduce the intake of these highly processed products can help reduce important risk factors for chronic disease.

Sodium, free sugars and saturated fat are considered nutrients of concern. This is because they can contribute to an increased risk of chronic disease when consumed in excess. Trans fat is also a nutrient of concern and is being addressed through a prohibition of partially hydrogenated oils in Canada.

Sodium is an essential nutrient. However, higher sodium intake is associated with higher blood pressure. 11 12 13 14 High blood pressure is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. 12 Sodium is present throughout the food supply, but by far the main contributors to dietary sodium intake are processed foods. In 2017, the main contributors of sodium in Canada were bakery products, mixed dishes, processed meats, cheeses, soups, sauces, dips, gravies, and condiments.15 In the population, 58% of all Canadians and 72% of children between the ages of 4 and 13 years consumed sodium above the recommended limits. 15

Free sugars are monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods and beverages by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, and sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates. 16 Free sugars do not include the naturally occurring sources of sugars found in intact or cut fruit and vegetables, and (unsweetened) milk. 16

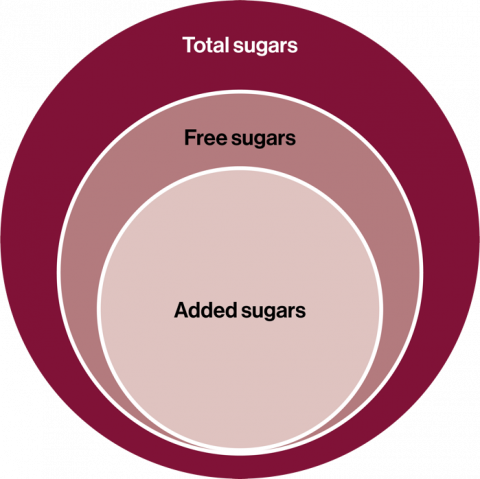

Beverages that contain free sugars (including 100% fruit juice) have been associated with a higher risk of dental decay in children. 18 Further, the intake of foods or beverages with added sugars has been associated with an increased risk of weight gain, overweight and obesity, and type 2 diabetes. 13 19 20 In 2015, sugary drinks , sugars, syrups, preserves, confectioneries, desserts (including frozen dessert), and bakery products were among the main sources of total sugars in the diets of Canadians. 21 These foods are also sources of free sugars. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between total, added, and free sugars.

To help reduce the intake of free sugars, the majority of total sugars intake should come from nutritious foods, such as intact or cut fruit and vegetables, and unsweetened milk.

Figure 1 : Relationship between added sugars, free sugars, and total sugars

Added sugars are all sugars added to foods and beverages during processing or preparation. All added sugars are also free sugars.

Free sugars are added sugars as well as sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices, and fruit juice concentrates.

Total sugars account for all sugars present in foods and beverages regardless of the source. This includes added, free, as well as the naturally occurring sources of sugars found in intact or cut fruit and vegetables, and unsweetened milk.

Trans fat intake has been associated with an increased cardiovascular disease risk and related risk factors. 17 26 Trans fats are naturally present in small amounts in ruminant animal-based foods such as dairy, beef, and lamb. They can also be produced industrially during the processing of vegetable oils. Historically, the major source of industrially produced trans fats was partially hydrogenated oils (PHOs). The prohibition of PHOs in Canada will effectively reduce trans fats in the food supply to the lowest level possible. It will also help achieve the public health objective of reducing trans fat intake by the vast majority of Canadians to less than 1% of total energy.

Saturated fat is a type of fat found in foods. It is found in animal-based foods, such as cream, butter, cheeses, and fatty meats as well as some vegetable oils such as coconut and palm kernel oil, and in coconut milk. One in two Canadians consume saturated fat above the recommended limit. 22 Lower intakes of foods that contain mostly saturated fat, through replacement with foods that contain mostly unsaturated fat, helps lower cardiovascular risk factors such as LDL-cholesterol. 12 13 17 19 23 24 25 In 2015, the major food sources of saturated fat were cheeses, red meat, butter and hard margarine. 22

Considerations

Sugary drinks, confectioneries, and sugar substitutes

Sugary drinks and confectioneries should not be consumed regularly.

In 2015, sugary drinks were the main sources of total sugars in the diets of Canadians, with children and adolescents (9 to 18 years of age) having the highest average daily intake. 21

Sugary drinks are beverages that can contribute to excess free sugars when consumed regularly. These include soft drinks, fruit-flavoured drinks, 100% fruit juice, flavoured waters with added sugars, sport and energy drinks, and other sweetened hot or cold beverages, such as iced tea, cold coffee beverages, sweetened milks, and sweetened plant-based beverages. While 100% fruit juice, sweetened milks or fortified soy beverage provide nutrients to the diet, these products can increase the intake of free sugars. Water, unsweetened milk or fortified soy beverage, and fruit should be offered instead.

Confectioneries—which include sweets such as candies, candy bars, fruit leathers, chocolate, and chocolate coated treats—were also top contributors of total sugars in the diets of Canadians in 2015. 21 These products provide high amounts of free sugars with little to no nutritive value. Confectioneries can also be sticky and adhere to teeth, which can increase the risk of dental decay.

Some confectioneries and sugary drinks (such as hot chocolate and specialty coffees and teas), can also contain cream or other ingredients with saturated fat. Confectioneries and sugary drinks are not needed for healthy eating and can displace nutritious foods in the diet. Promoting the consumption of water instead of sugary drinks, and reducing the intake of confectioneries to a minimum, are important ways to help Canadians decrease free sugars intake and reduce the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and dental decay.

Sugar substitutes do not need to be consumed to reduce the intake of free sugars.

Some foods and beverages (such as some fat-free yogurts and diet soft drinks) are sweetened with sugar substitutes such as aspartame, saccharin, sugar alcohols and purified stevia extract, instead of free sugars. In Canada, these sugar substitutes are regulated as “sweeteners,” a type of food additive . Food additives, including sweeteners, are subject to strict controls under Canada’s Food and Drugs Act and its Regulations to ensure their safety. The sweeteners that have been approved in Canada include sugar alcohols and high-intensity artificial or naturally sourced sweeteners. However, as there are no well-established health benefits associated with the intake of sweeteners, 19 27 28 nutritious foods and beverages that are unsweetened should be promoted instead.

Publically funded institutions

Foods and beverages offered in publically funded institutions should align with Canada’s Dietary Guidelines.

To create supportive environments for healthy eating, publicly funded institutions should offer healthier options that align with Guideline 1 and limit the availability of highly processed foods and beverages, such as sugary drinks and confectioneries. 29 30 31 32 Workplaces should take a similar approach by providing access to healthier options. Another way to create supportive environments is to limit the promotion of highly processed products in retail settings such as grocery and convenience stores. 30 These strategies can help promote lifelong healthy eating habits.

Alcohol

There are health risks associated with alcohol consumption.

Alcoholic beverages can contribute a lot of calories to the diet with little to no nutritive value. When alcohol is mixed with syrups, sugary drinks such as soft drinks and fruit-flavoured drinks, or cream-based liquors, they can be a significant source of sodium, free sugars, or saturated fat.

Further, the substantial disease burden attributed to alcohol intake is a leading global health concern. 33 There are well-established health risks associated with long-term alcohol consumption, including increased risk of many types of cancer—liver, oesophageal, mouth, pharynx, larynx, colorectal, and breast (post-menopausal)— and other serious health conditions (such as hypertension and liver disease). 7 8 9 10 27 34 35 36

Non-fatal health and social problems are also associated with drinking alcohol. 35 36 The economic costs of alcohol-related harm in Canada are estimated to be more than $14 billion, with about $3.3 billion directly related to health care costs. 37 In 2016, there were at least 3,100 deaths related to alcohol in Canada. 38 In the same year, about 77,000 hospitalizations in Canada were due to conditions entirely caused by alcohol. 39

People who do not consume alcohol should not be encouraged to start drinking. 35 If alcohol is consumed, Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines can be used to provide information on how to reduce the risk of alcohol-related harms in both the short and long term. These guidelines set a limit, not a target. 35 If all Canadian drinkers were consuming alcohol within the Guidelines, alcohol-related deaths could be reduced. 35

| Finding | Source of evidence |

|---|---|

| Sodium | |

| Association between decreased intakes of sodium and decreased blood pressure | American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2013: Guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the ACC/AHA task force on practice guidelines |

| World Health Organization 2012: Guideline: sodium intake for adults and children | |

| National Health and Medical Research Council 2011: A review of the evidence to address targeted questions to inform the revisions of the Australian Dietary Guidelines | |

| Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee 2010: Report of the DGAC on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans | |

| Free sugars | |

| Association between increased intakes of sugar sweetened beverages and increased risk of weight gain, overweight and obesity | World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research 2018: CUP expert report: energy balance and body fatness |

| Association between increased intakes of sugar-containing beverages and increased risk of dental decay in children | Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition 2015: Carbohydrates and health report |

| Association between increased intakes of added sugars (from food and/or sugar-sweetened beverages) and increased obesity risk and type 2 diabetes risk | Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee 2015: Scientific report of the DGAC: advisory report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture |

| Association between increased intakes of sugar-sweetened beverages and increased risk of obesity among children | Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee 2010: Report of the DGAC on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans |

| Saturated fat replacement | |

| Association between replacement of saturated fat with monounsaturated fat and lowered cardiovascular risk factors | World Health Organization 2017: Health effects of saturated and trans-fatty acid intake in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis |

| World Health Organization 2016: Effects of saturated fatty acids on serum lipids and lipoproteins: a systematic review and regression analysis | |

| Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2010: Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition – Report of an expert consultation | |

| Association between replacement of saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat and lowered cardiovascular risk factors | World Health Organization 2017: Health effects of saturated and trans-fatty acid intake in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis |

| World Health Organization 2016: Effects of saturated fatty acids on serum lipids and lipoproteins: a systematic review and regression analysis | |

| Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2010: Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition – Report of an expert consultation | |

| Association between replacement of saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat and lowered cardiovascular disease risk | Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee 2015: Scientific report of the DGAC: advisory report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture |

| Association between replacement of saturated fat with unsaturated fat (especially polyunsaturated fat) and lowered cardiovascular risk factors | Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee 2015: Scientific report of the DGAC: advisory report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture |

| American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2013: Guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the ACC/AHA task force on practice guidelines | |

| Association between replacement of saturated fat with unsaturated fat (type not specified) and lowered cardiovascular risk factors | Health Canada 2012: Summary of Health Canada’s assessment of a health claim about the replacement of saturated fat with mono- and polyunsaturated fat and blood cholesterol |

| Association between replacement of saturated fat with monounsaturated fat and lowered cardiovascular risk factors and type 2 diabetes risk | Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee 2010: Report of the DGAC on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans |

| Processed meat | |

| Association between increased intakes of processed meat and increased risk of cancer | International Agency for Research on Cancer 2018: IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans – Red meat and processed meat |

| Association between increased intakes of processed meat (per 50 grams/day) and increased risk of colorectal cancer | World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research 2018: CUP report: colorectal cancer |

| * Convincing findings are findings graded ‘High’ by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society, and the World Health Organization; findings graded ‘Strong’ by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; findings graded ‘Sufficient’ by Health Canada; findings graded ‘Group 1: Carcinogenic’ by the International Agency for Research on Cancer; findings graded ‘Adequate’ by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition; findings graded ‘Convincing’ by the Food and Agricultural Organization, and the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute of Cancer Research; and findings graded ‘A’ by the National Health and Medical Research Council. | |

References

- Footnote 1

- Moubarac JC, Batal M, Martins AP, Claro R, Levy RB, Cannon G, et al. Processed and ultra-processed food products: Consumption trends in Canada from 1938 to 2011. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2014;75(1):15-21. 1

- Footnote 2

- Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. The nutrition transition: worldwide obesity dynamics and their determinants. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(Suppl 3):S2-S9. 2

- Footnote 3

- Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804-814. 3

- Footnote 4

- Tjepkema M. Adult obesity. Health Rep. 2006;17(3):9-25 4

- Footnote 5

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective[Internet]. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2011 [cited 2018 Sep 14]. 5

- Footnote 6

- Public Health Agency of Canada. How healthy are Canadians? A trend analysis of the health of Canadians from a healthy eating and chronic disease perspective [Internet]. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2016 [cited 2018 Sep 14]. 6

- Footnote 7

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and colorectal cancer. Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2018. 7

- Footnote 8

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and liver cancer. Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2018. 8

- Footnote 9

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and breast cancer. Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2018. 9

- Footnote 10

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and oesophageal cancer. Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2018. 10

- Footnote 11

- World Health Organization. Guideline: sodium intake for adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. 11

- Footnote 12

- Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, de Jesus JM, Miller NH, Hubbard VS, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S76-S99. 12

- Footnote 13

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010: to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Washington: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2010. 13

- Footnote 14

- National Health and Medical Research Council. A review of the evidence to address targeted questions to inform the revisions of the Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2011. 14

- Footnote 15

- Health Canada. Sodium Intake of Canadians in 2017 [Internet]. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2017 [cited 2018 Sep 14]. 15

- Footnote 16

- World Health Organization. Guidelines: Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. 16

- Footnote 17

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Fats and Fatty Acids in Human Nutrition: Report of an Expert Consultation. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2010. 17

- Footnote 18

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. SACN Carbohydrates and Health Report. Norwich: Public Health England; 2015. 18

- Footnote 19

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: advisory report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. Washington: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2015. 19

- Footnote 20

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, nutrition and physical activity: energy balance and body fatness. Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2018. 20

- Footnote 21

- Langlois K, Garriguet D, Gonzalez A, Sinclair S, Colapinto CK. Changes in total sugars consumption among Canadian children and adults. Health Reports. 2019; 30(1): 10-19. 21

- Footnote 22

- Health Canada. 2015 Canadian Community Health Survey – Nutrition. [Internal analysis]. 22

- Footnote 23

- Health Canada. Summary of assessment of a health claim about the replacement of saturated fat with mono- and polyunsaturated fat and blood cholesterol lowering [Internet]. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2012 [cited 2018 Sep 14]. 23

- Footnote 24

- Mensink RP. Effects of saturated fatty acids on serum lipids and lipoproteins: a systematic review and regression analysis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. 24

- Footnote 25

- Te Morenga L, Montez JM. Health effects of saturated and trans-fatty acid intake in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One. 2017;12(11):e0186672. 25

- Footnote 26

- Brouwer IA. Effect of trans-fatty acid intake on blood lipids and lipoproteins: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. 26

- Footnote 27

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2018. 27

- Footnote 28

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and bladder cancer. Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2018. 28

- Footnote 29

- Niebylski ML, Lu T, Campbell NR, Arcand J, Schermel A, Hua D, et al. Healthy food procurement policies and their impact. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(3):2608-2627. 29

- Footnote 30

- Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253-272. 30

- Footnote 31

- Hawkes C, Smith TG, Jewell J, Wardle J, Hammond RA, Friel S, et al. Smart food policies for obesity prevention. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2410-2421. 31

- Footnote 32

- Raine K, Alkey K, Olstad DL, Ferdinands R, Beaulieu D, Buhler S, et al. Healthy food procurement and nutrition standards in public facilities: evidence synthesis and consensus policy recommendations. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(1):6-17. 32

- Footnote 33

- Global Burden of Disease 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. Epub 2018 Aug 23. 33

- Footnote 34

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancers of the mouth, pharynx, and larynx. Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2018. 34

- Footnote 35

- Butt P, Beirness D, Stockwell T, Gliksman L, Paradis C. Alcohol and health in Canada: a summary of evidence and guidelines for low risk drinking. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2011. 35

- Footnote 36

- Public Health Agency of Canada. The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2015: Alcohol consumption in Canada [Internet]. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2016 [cited 2018 Nov 28]. 36

- Footnote 37

- Rehm J, Baliunas D, Brochu S, Fischer B, Gnam W, Patra J, et al. The costs of substance abuse in Canada, 2002. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2006. 37

- Footnote 38

- Statistics Canada [Internet]. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2016 [cited 2018 Oct 23]. CANSIM tables. 38

- Footnote 39

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Alcohol harm in Canada: Examining hospitalizations entirely caused by alcohol and strategies to reduce alcohol harm [Internet]. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2017 [cited 2018 Oct 23]. 39